1876

The St. Elisabeth institute was a place where orphan girls and sick women were cared for. The orphanage originated from the R.C. Maagdenhuis, which was an orphanage that had existed since 1628 and was located on the Spui in Amsterdam.

The R.C. Maagdenhuis had two problems. The first problem was that it housed too many elders (or orphans who, as they grew older, for whatever reason, did not leave the house). The regents preferred to see them leave, but it was difficult to find a place for them. Besides, due to developments of the second half of the 19th century, the number of orphan girls declined sharply.

After 1876, two new regents were appointed. Mr Van Rijckevorsel and Mr Sträter. They made the first plans to set aside money to establish a new institute.

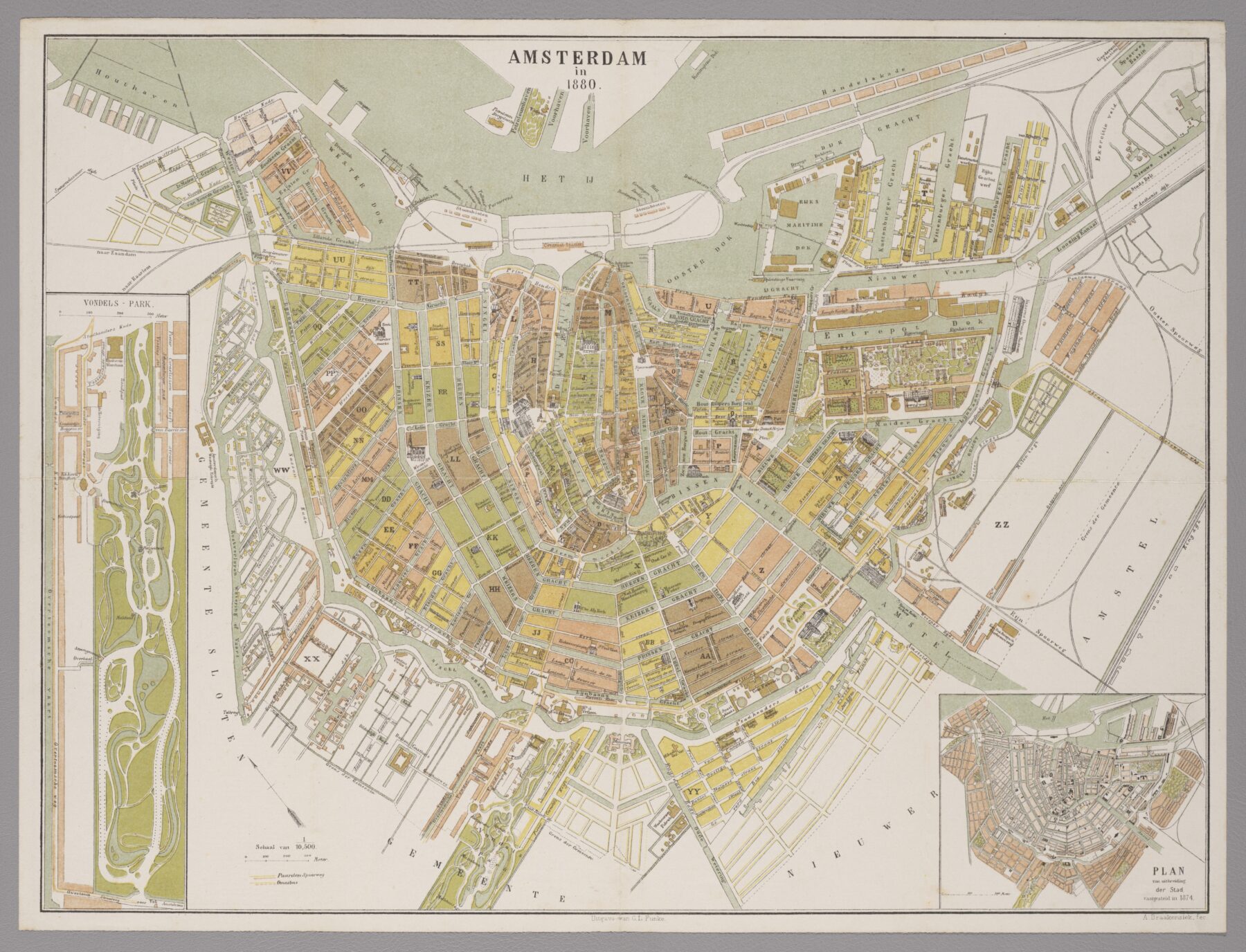

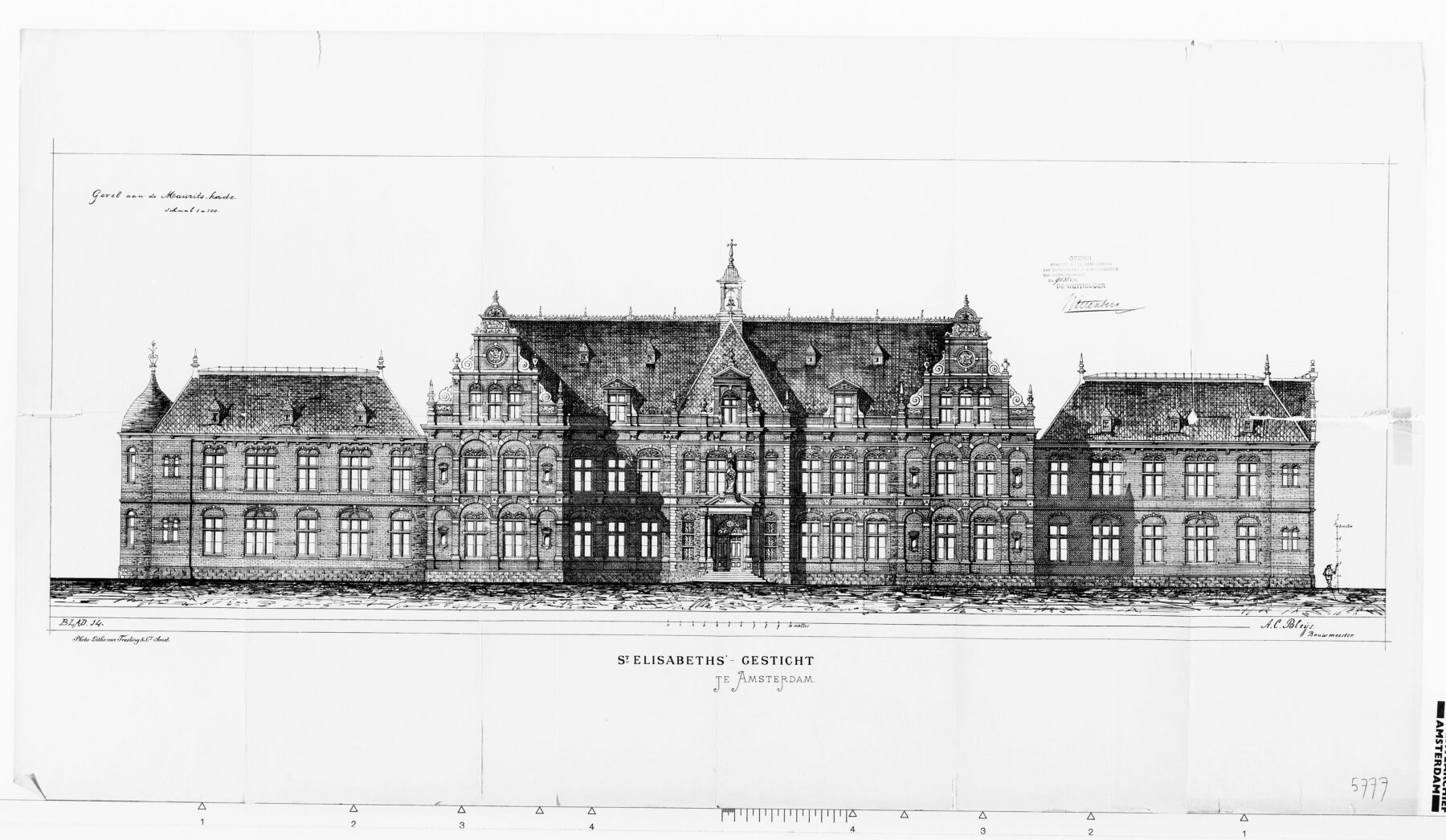

City expansion in Amsterdam East had begun. This caused land prices to rise rapidly. The institute was to be built behind the Mauritskade, where the Oosterpark was also being laid out. The surrounding streets were already under construction, as was the civilian hospital (now Hotel The Manor), which had also purchased four hectares.

1886

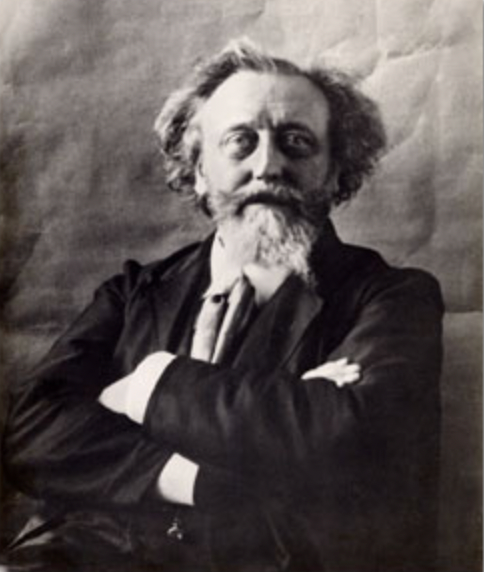

On July 15, 1886, a meeting took place to decide who would design the building. By means of voting, Mr. Adrianus Cyriacus Bleijs was elected as the architect.

Adrianus Bleijs (1842-1912) was a talented Roman Catholic architect, born in Hoorn. He had completed his education in Antwerp but quickly returned to the Netherlands afterward. He briefly worked for Mr. Pierre Cuypers (architect of, among others, the Rijksmuseum), but this was short-lived. Bleijs moved back to Hoorn where he started his own business. One of his most important works is the St. Cyriacus Church in Hoorn. He did not call himself an architect but a master builder.

He was one of the few Catholic architects who did not build exclusively in the Neo-Gothic style. He believed that architects should master and apply multiple styles, depending on the project. He built churches with features from the Renaissance and Baroque periods. This met with much resistance. However, it did not deter him.

After living in Hoorn for about 15 years, Bleijs moved with his wife and nine children to Amsterdam, where he designed, among other things, the St. Nicholas Church located near the central station.

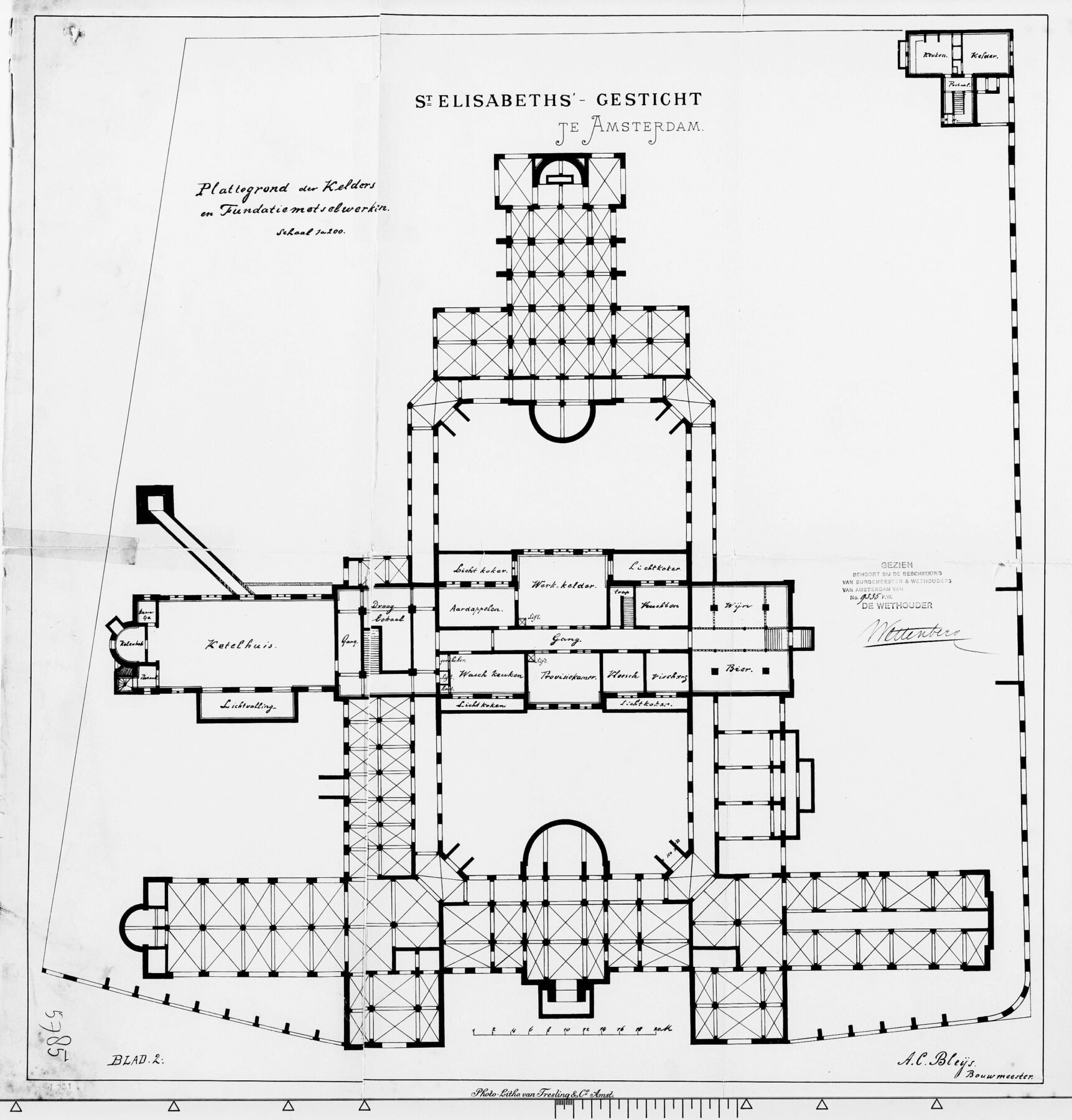

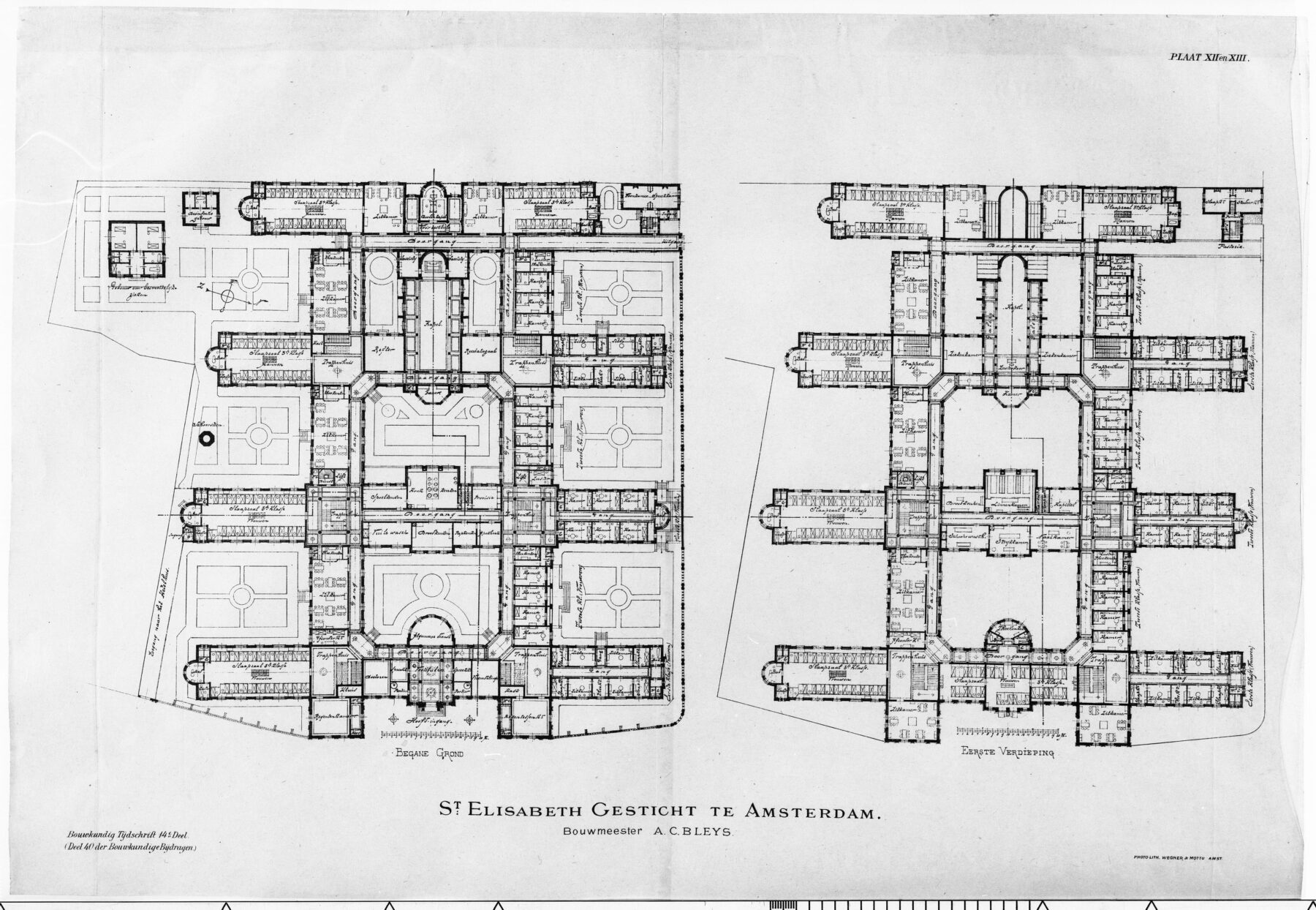

Bleijs used a corridor system combined with a pavilion system in this building. Bleijs’s design is a rectangle, with the main entrance on one short side and the chapel on the other short side. Previously, the main entrance was on the Mauritskade. The surrounding corridors ran along the rooms, with four halls protruding on either side. These were the dormitories. Next to the corridors were sitting rooms, all of which had courtyards.

Have you already looked closely at the stairs in the lobbies? The old logo of St. Elisabeth is still there, where an S and an E are intertwined into a beautiful emblem of the institute.

1888

In 1888, the doors of the St. Elisabeth Institute were opened.

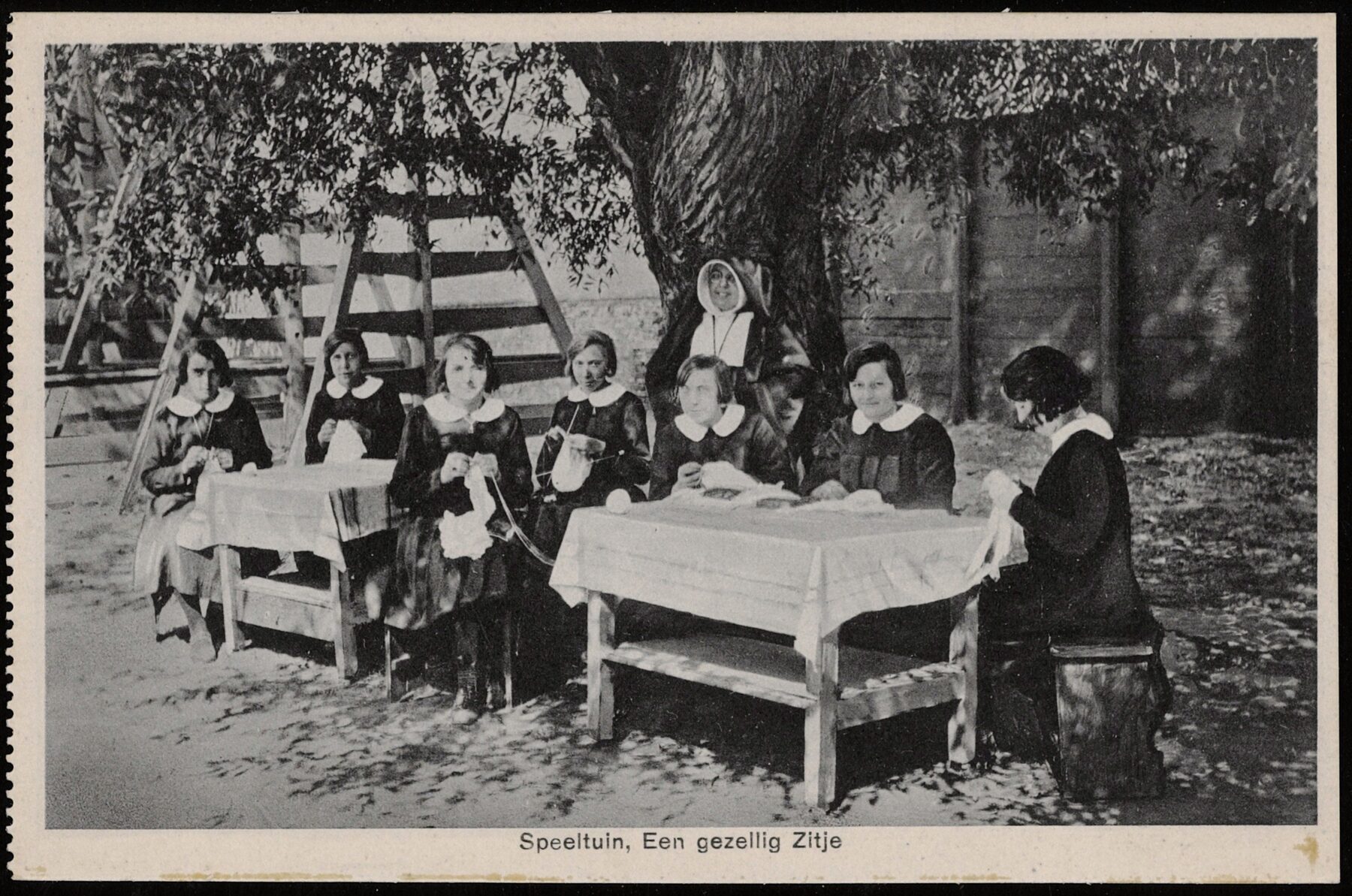

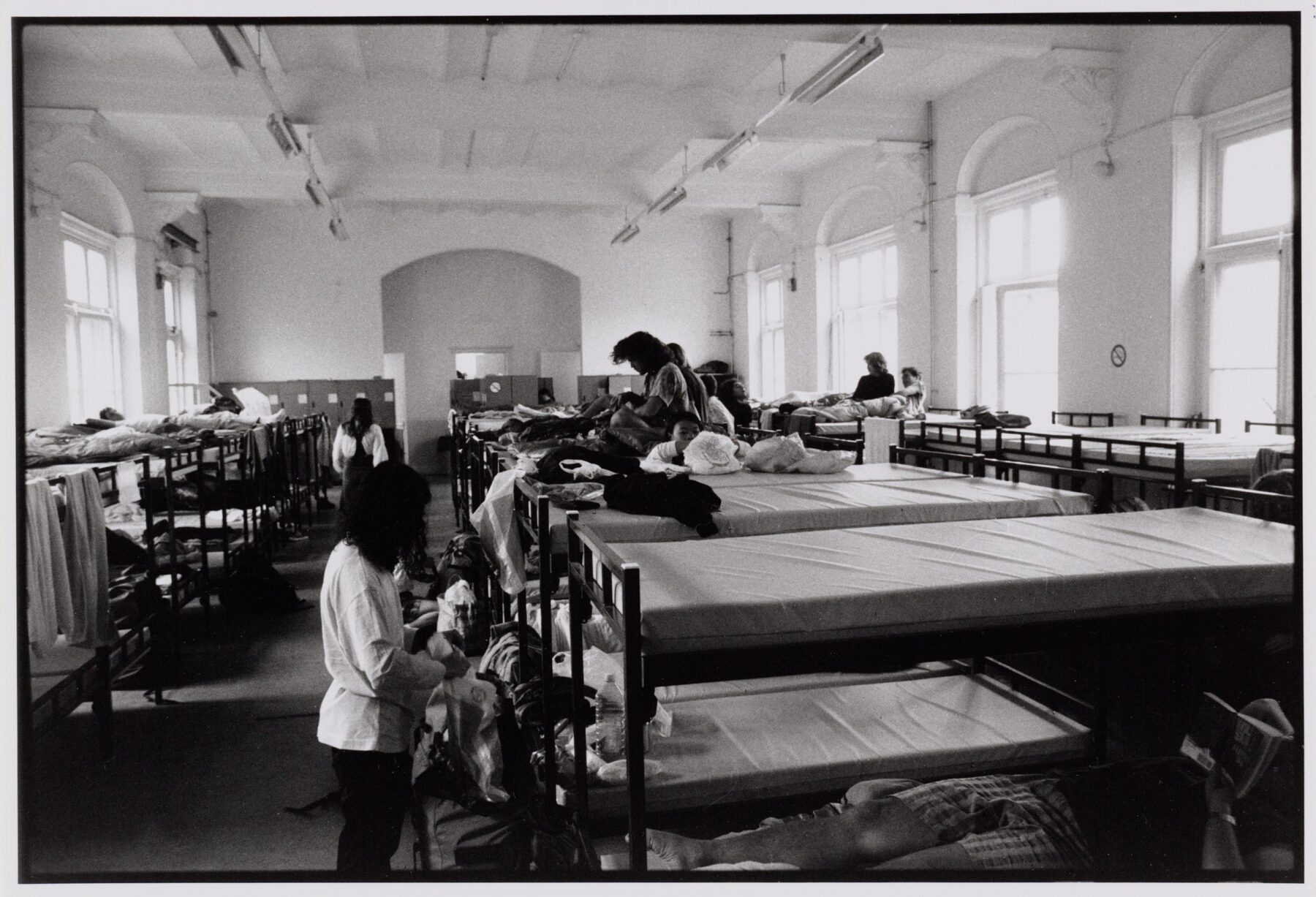

The right half of the building was mainly occupied by class patients, which are residents of the first and second classes. They slept here for a fee and had a lot of privacy and freedom. Residents of the third and fourth classes did not pay and slept together in the dormitories. In return, they were kept busy with household tasks during the day.

In total, 269 patients stayed at the institute.

In a dormitory, the beds were arranged in two rows. Each dormitory also had a sitting room where the patients could sit during the day. These were spacious rooms, equipped with toilets and tea kitchens. At the ends were the toilets, a bathroom, and a place for the nurse.

1901

In 1901, a hall was also set up for the orphan girls from the Maagdenhuis. Troublesome girls were raised here.

The nurses came from the ‘Sisters of Mercy from Tilburg’. There were about 54 sisters, so there were about 5 patients per sister. Most of the sisters slept in the attic in the middle section of the building. This was above the domestic wing, where the ironing room, sewing room, bread kitchen, etc., were located. The residents of the institute and the sisters gathered daily in the chapel for their prayers. Underneath the pavilion was the boiler room with central heating. The chimney is detached from the building.

The daily management of the institute was led by the mother superior, the rector, and the physician, not by regents as at the R.C. Maagdenhuis. This was because the activities in the institute were more specialized. They resided in the adjacent house next to the institute.

Originally, the institute was supposed to have a men’s section as well. It was to be located next to the rectory, in front of the chapel, and accessible via a separate corridor. There was also an effort to create more classrooms, but that too was unsuccessful. The fact that the institute was unfinished was not uncommon for that time. There was so much construction happening then that it became difficult to complete everything.

1924

As time passed, the St. Elisabeth institute began to cost more and more money. The number of patients decreased, and the high number of sisters living there no longer offset the expenses. Additionally, the maintenance costs of the building and central heating were quite high. In 1924, the institute still had 167 places.

1944

During the Second World War, the Germans seized the Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis (OLVG). As a result, the obstetrics department was temporarily housed in the institute. Unfortunately, in 1944, the St. Elisabeth institute also fell into the hands of the Germans. After having to live near Leidseplein for a while, the residents were able to return a year later in 1945.

1953

In 1953, the number of residents stood at 175. By then it had become more of a nursing home than an institute. During this time, there were temporarily more orphan girls living there, mainly because the building of the R.C. Maagdenhuis on the Spui had been sold to the municipality of Amsterdam. The word “institute” also began to carry a negative connotation, so the name was changed to “House Elisabeth.”

1969

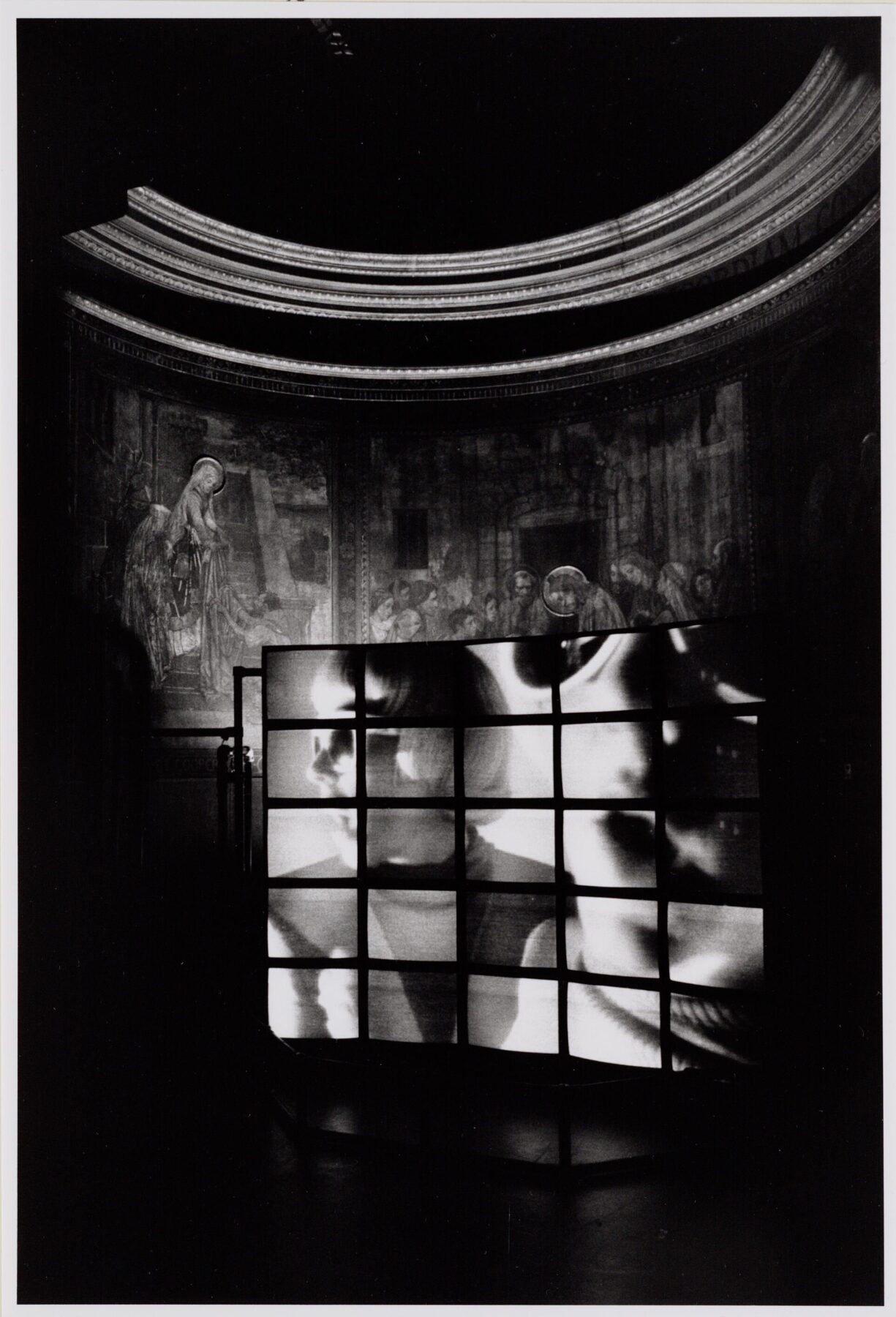

Still, the house began to show signs of aging. To continue its existence, the house had to undergo a modernization process. The costs were becoming exceedingly high, and the nursing home was no longer financially self-sufficient. In 1969, the property and lease were taken over by the Foundation for Nursing Homes in Amsterdam. The chapel was converted into a recreation room.

1982

Ultimately, in 1982, House Elisabeth was also sold to the municipality of Amsterdam. The residents departed, and several historical features of the building were removed, such as the St. Elisabeth statue and the foundation’s memorial stone.

To prevent the building from remaining vacant, the municipality invited squatters into the premises. Among them were many Dam and Vondelpark sleepers, who were hippies sleeping in public spaces. Besides, a sleep-inn was established, where people could get a bed for a few guilders.

1992

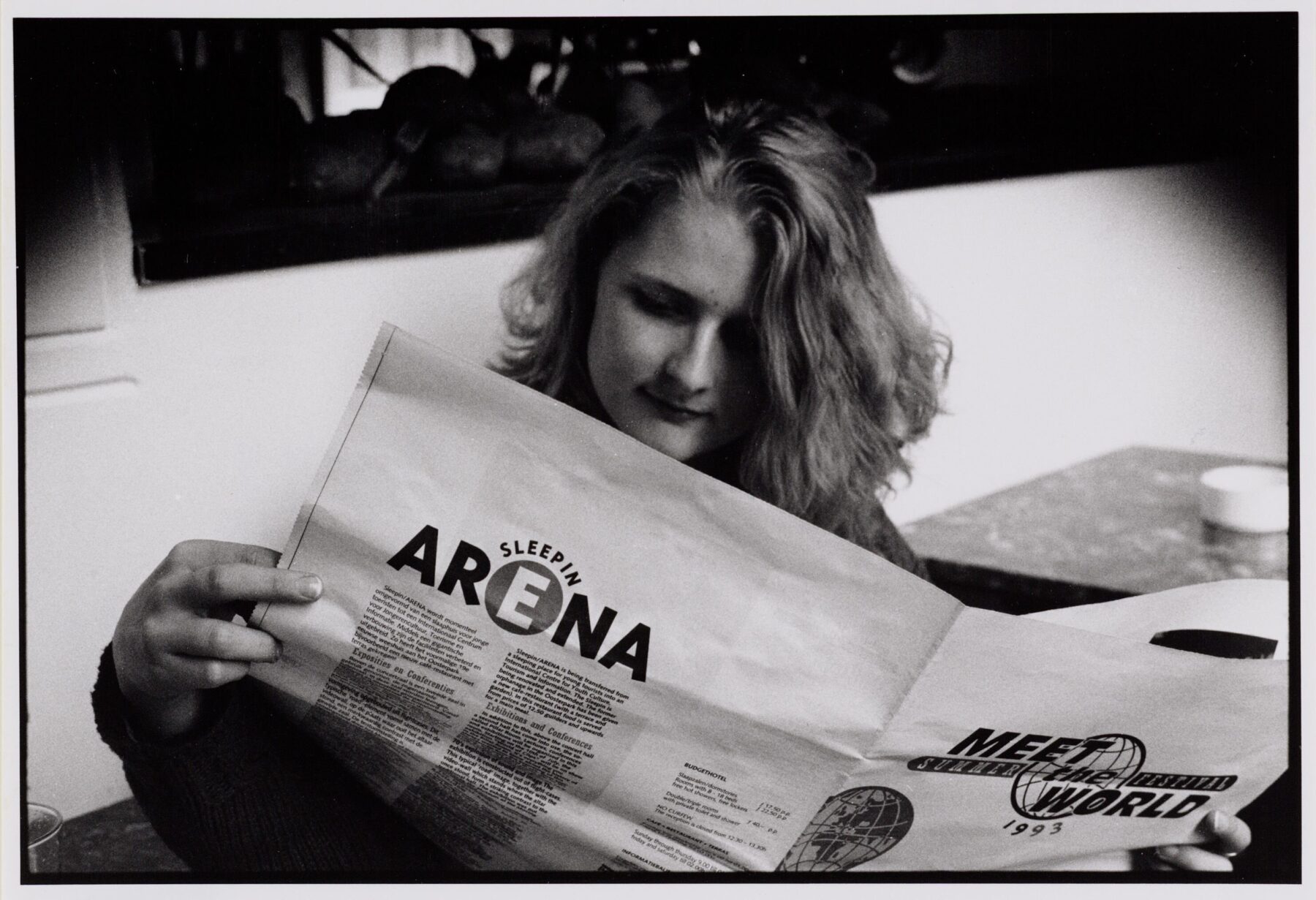

In 1992, the municipality ended their subsidy for the Sleep-inn. Alternative sources of income needed to be found.

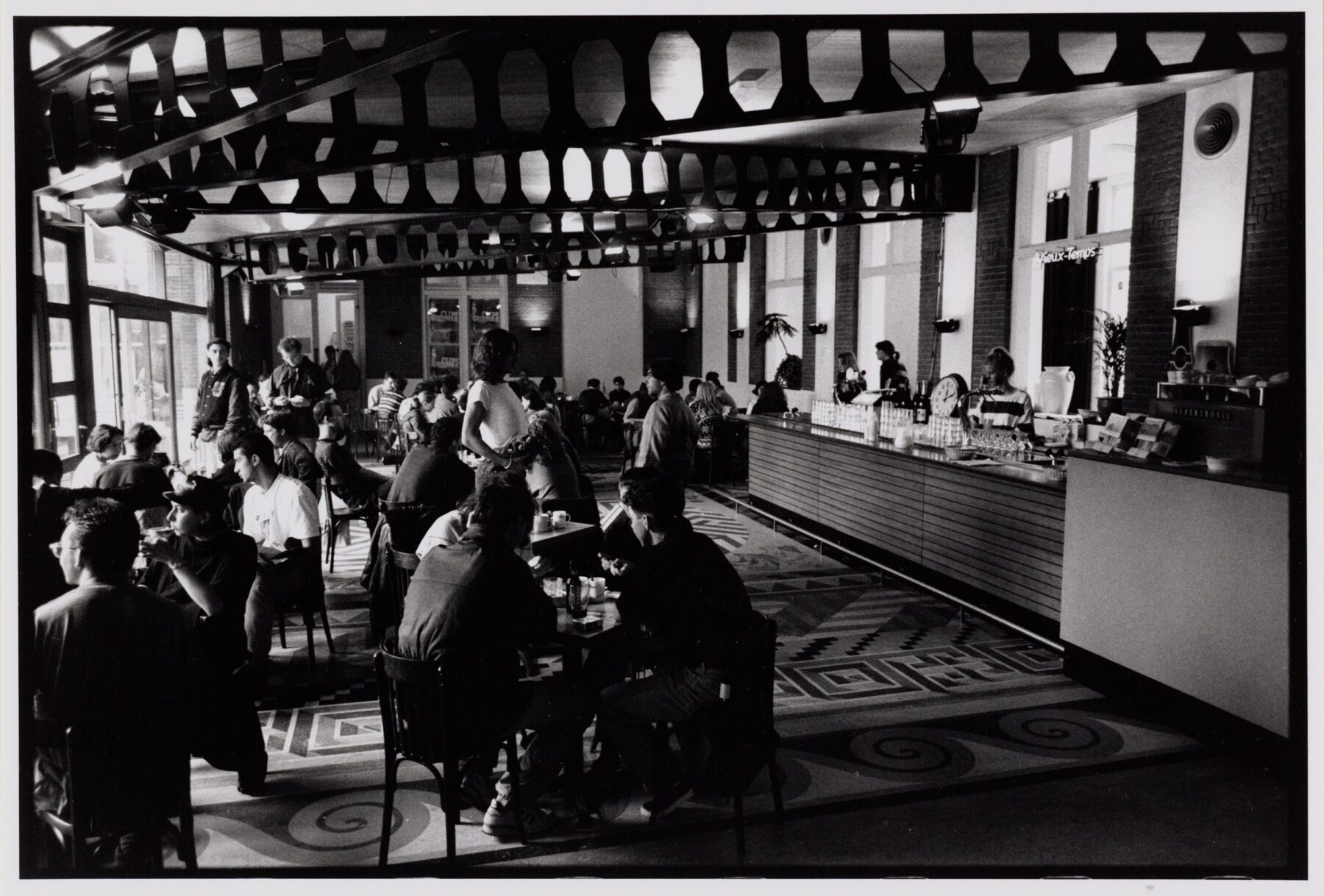

Paul Hermanides took over the building and opened an international center for youth culture and tourism called Arena. In addition to the hostel, a café/restaurant, performance stages, and a club were added.

Memorable parties and concerts by major artists have taken place here. Think of Oasis, Norah Jones, and Alicia Keys.

1996

In 1996 the name Arena was changed to Hotel Arena. The hotel now had two stars.

2002

In 2002 it was time for a major renovation. Various halls and attics were converted into hotel rooms. Due to the more than 100-year-old monumental building, each room has its own nooks and layouts, but all with the same design and feeling. Due to the improved service, the hotel now had three stars. And in 2010, this even became four!

Also the chapel has gone through many changes over the years.

2015

In 2015, the next major renovation began as the hotel underwent significant expansion. The hotel was extended towards the Oosterpark, following the original design by the architect Adrianus Bleijs.

A parking garage, café/restaurant, six modular event studios, and an entirely new hotel wing were added. Additionally, the chapel was renovated and better insulated.

The renovation took two years, so in 2017, it was time for the grand opening!

2022

In 2022, the hotel celebrated its thirtieth anniversary with a new reception and an additional suite in the hotel. The top suite is our 141st room and one of our finest accommodations.

Present

And here we are.

The building carries many stories. From the Catholic sisters who were always ready to help, to the partying youngsters who wanted to celebrate their freedom through art, music, and culture.

It is a building that represents what Amsterdam is. A small metropolis where respect and freedom are held in high regard. That hospitality is exactly what we want to share with our guests.